Performance Matters

Don’t succumb to the cynicism that tells you it doesn’t

“In the dark times Will there also be singing? Yes, there will also be singing About the dark times.”

Yesterday somewhere between 3 to 5 million people engaged in protests nationally, from big cities to small towns, red and blue, across the country, with additional demonstrations of support taking place around the world. This was not the well choreographed protest of 2017, which is the only other recent mass demonstration in the U.S. to reach such high participation numbers. It was messy in some ways, highly decentralized, and a little chaotic. (I think this is good, by the way. But more on that another week.) This weekend’s protest also differed from 2017 in that it stood on the framework of months of build-up among smaller demonstrations and local organizing efforts. Prior to this weekend, there had already been twice as many protests in 2025 relative to this time in 2017. Saturday’s events are also being positioned by organizers as a beginning rather than as a singular, historic day. This is significant in shaping a public mindset that is prepared for a long haul and isn’t deluded into expecting immediate results from a single day of action.

I think it’s important to begin with this data, because it is difficult to build inspiration when we are often steeped in cynicism, and it is difficult to build endurance when we are accustomed to instant gratification. We need constant reminders, both that our actions matter and are part of something bigger than we are able to see from our individual vantage points, and that we have to keep working, because no single action alone, even when carried out by many people, changes the landscape immediately.

Beyond the data, though, I think the texture of these events is also important to understand, as is the way we tell the story of how change happens.

Saturday was overcast and at times rainy here in New York. One of the things that struck me, walking in the drizzle, was how much the musicians sprinkled through the crowd mattered. When the skies are blue and the sunshine is abundant, events like this feel easy and exuberant. They take on a sort of ordained quality that may be exhilarating but often fades quickly as the sun sets and the crowd disperses. The energy sunshine bestows feels externally granted, so it’s easy to unconsciously presume that the momentum of the world will carry us forward, rather than expecting that our own effort and determination will be necessary. Walking under grey skies in the rain requires a different kind of internal motivation and a different level of communal commitment. The drums and the megaphones become much more important, because we need their beat and their volume to fortify our inner resolve and our awareness of one another.

The significance of the drummers and other moments of public display throughout the day has me thinking about the role of performance in affecting change and the way in which this has become muddled by our own descriptive language. The notion of “performative action” has evolved recently into a powerful verbal tool for identifying hollow gestures that are intended to capitalize, either reputationally or financially, on a public veneer of allyship and solidarity that is not backed by action or, worse, that actually serves to mask direct harm.

In an age when it is uniquely easy to reach a massive audience through gestures that require very little actual time, investment, or sacrifice, and when social media has created a culture of personal branding, it is genuinely important to be able to distinguish between sincere efforts at social change and actions that are merely market-driven click-bait, crafted to elevate cultural clout. As the journalist, Adam Harris, noted in an essay for The Guardian today, detailing the history of such superficial corporate gestures and their inevitable backlash,

“Values are only as good as their durability under pressure; and many of America’s largest companies proved an equitable, inclusive workplace was never one of their core values to begin with.”

This has been true, not only for corporations, but also on an individual level. In an economy of image, perception easily becomes malleable and meaningless, allowing our identities and social relationships to slip into a version of reality that is highly curated and difficult to trust.

It is important, therefore, to recognize the fragility of these superficial gestures. It is also important to prepare for the ease with which actions that are taken solely for the purpose of riding a cultural wave and constructing the appearance of solidarity are undone. The companies that declared diversity a core value and sold rainbow emblazoned water bottles and Black Lives Matter t-shirts when it was profitable to do so are now casually tossing these self-proclaimed values aside, because they have become a liability rather than an asset.

This should not be surprising. Corporations are by definition motivated by profit, not by social good, and it’s unwise to allow our perceived alignment with their branding at any given time to blind us to this fact. That said, it is worth trying to push companies toward responsible and ethically grounded practices, because they hold enormous power to both shape and reflect public sentiment. But we have to do this with an eyes-wide-open understanding that corporate choices, even when we approve of them, will always be inherently subject to the whims of a shifting zeitgeist. Our task is to do what we can to shape the zeitgeist.

Similarly, it is important to be able to recognize hypocrisy, not only in companies but in personal relationships and in our leaders. Making the discrepancies between the words we are offered when a spotlight is available and the actions taken behind the scenes visible is essential to personal and political accountability.

However, this weekend, as I intentionally kept pace with one of the drummers along 5th Avenue and observed, not only the usual array of handmade signs, but also some of the bolder gestures that punctuated the day, I found myself wondering if using the word “performative” to describe gestures of hypocrisy might be a fatal mistake worthy of renegotiating with more direct and pointed language. Because performance is powerful and necessary and not inherently hollow.

We have come to understand performative gestures as those actions marked by a desire for attention and approval that is shallow at best and deceitful at worst—gestures that are motivated by profit, power, and self-aggrandizement not by sincerity. The problem is that this is not actually the primary definition of the word “performative,” and its use potentially sacrifices a powerful tool. This definition was only added to dictionaries very recently to reflect shifting usage. The first instance of “performative” as a description of superficiality is noted by the OED in 1996, with more popular use emerging, notably alongside social media, in 2014 and only becoming pervasive in the past five years. By contrast, the primary definition of “performative,” which dates back to the 1920’s, refers very simply to any public utterance or action. It also has an obvious connection to artistic expression, which is why the musicians I walked with on Saturday seem especially important here.

Language evolves. But I worry that by using this particular word, in lieu of more direct words like “hypocrisy,” we’ve unintentionally deprived ourselves of one of the most powerful and meaningful tools available to any cause of social or political change.

Performance, when understood through its original definition, isn’t inherently fake or fragile. On the contrary, performance is one of the most robust mechanisms for individual and collective learning, memory, and transformation. Whether we are referring to artistic performance in all its forms or to powerful oratory, the role of performance—of public expression—first and foremost, is to move people. There is a reason that, across cultures and throughout history, performance has been present in some form wherever there are humans. From its earliest roots in oral storytelling, myth, and ceremony, performance has always served to shape our memories, our understandings, our values, and our relationships. True performance does this, not by being fake or fragile, but by tapping into our deepest and most authentic human experiences in ways that bring forth self-recognition and a feeling of common connection.

The goal of performance is always to transform the audience in some way, and that, in itself, is consequential. This is not only true of performance in its most obvious artistic and theatrical forms. It is also why we learn about history within the context of the great speeches and powerful images that both shaped the course of events in the past and frame our understanding of and connection to those events today. Public expression creates shared experiences and, when most effective, provokes shared reactions. There is a reason that the concepts of catharsis and empathy both have their linguistic roots in art—catharsis from the emotional release that occurs through a powerful shared experience, often typified by our feeling of synchrony with a character in a climactic theatrical or literary event, and empathy from the exploration of art’s power to ignite a feeling of emotional connection with an object, such as a painting or a sculpture.

Performance is powerful. This isn’t just nerdy linguistic nitpicking. It is central to how we understand and activate change. This is perhaps most evident in extremism, which almost always relies heavily on the power of visible, public, theatrical impact to incite fear. What, after all, are KKK robes if not shockingly provocative costumes, designed to spark a visceral emotional response. Painting a swastika on the wall of a synagogue or hanging a noose outside a college dorm are similar acts of public performance, crafted very specifically and intentionally to cultivate profound rage and terror. We don’t describe these gestures as “performative,” because they are so effective at conveying the violent actions that they signify, and, most importantly, because history teaches us that these symbols are not empty gestures but very real threats.

Powerful performance is not limited to the incitement of fear and anger though. Performance also has a long and effective history of inciting strong feelings of inspiration and connection. The effective use of performance has been essential to provoking a more just and inclusive society time and again. Gestures of performance can stir terror, but they can also ignite our highest aspirations—Inez Millholland draped in white atop a white horse, for example, or a procession of Black men carrying signs emblazoned with the words, “I Am a Man,” or countless examples throughout the ACT UP movement, which was largely shaped by compelling public art. Additionally, each of the many speeches, now seared into our historical memory, are also, in essence, performances that moved people so significantly and demonstrably that they changed the course of events.

The difference between these powerful acts of performance—whether designed to terrorize or to inspire our sense of common humanity—and the gestures that we now deem "performative" seems stark in this context. The former is steeped in sincere and visceral intention, which radiates genuine feeling and a commitment to action. The latter is thin, insincere, and evaporates the moment any actual sacrifice is required.

This distinction is important. We need to be able to discern the difference between the lasting force of sincere conviction and the flimsiness of an easy, one-off image crafting gesture. But the language we currently use to mark this distinction—performance vs performative—is subtle and confusing, isn’t it?

The consequence of deploying such easily conflated terms has, I think, been the development of a widespread skepticism and quick questioning of any and all public-facing gestures. This deprives us of the ability to benefit, on a personal level, from the meaningful and transformative power of true performance, and it cuts short the potential to leverage the impact of performance to fuel real connection, action, and change.

We have inadvertently cultivated a perception that only actions with an immediate and perceptible practical outcome are sincere or valuable, and we have fostered a tendency to view everything that does not offer instant proof of sincerity and direct impact as potentially self-serving and meaningless.

But performance is essential to change. It is surely important to demand accountable action as well and to distinguish between real and contrived public statements. But viewing all public gestures that don’t result in clear and immediate practical results as suspect creates a cynicism and a short-sightedness that, ironically, undercuts our ability to affect real change. Moving people to action first requires that we move them emotionally, spiritually, and intellectually. And this is impossible to do if we dismiss all inspiration or any efforts that engage a wide audience as insincere or fraudulent.

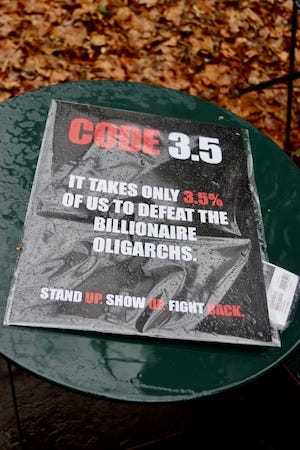

I’ve referred previously to the research, which is now being spread widely, that defeating authoritarian power requires sustained resistance, building over time, and culminating in participation from at least 3.5% of the population.

While it is encouraging to think that 3.5% is a relatively small number compared to the entire population, it is still important to recognize that this is substantially more massive mobilization than we have ever seen in the U.S., and we won’t reach it if we expect perfection and instant impact every step of the way. Nor will we reach it if we’re not willing to inspire people, and inspiration is most often accomplished through the various forms of public speech and performance. We ignite the public by speaking publicly and by creating moving public spectacles.

The performer, Nick Cave, recently wrote of the power of concerts explaining,

“Live music is a ritual that evokes a common emotional response to which we attach our singular experiences. When I perform on stage, I can see these unique and particular feelings play out on each face…The concert becomes powerfully and empathetically transactional as we experience together the therapeutic nature of the music. As the show evolves, a to-ing and fro-ing of kindness emerges, energized by our mutual regard, and the healing begins…We heal by acknowledging our emotions and test our heart’s resilience by lingering within the unbearable. It is something music can help us do. We find our hearts are much stronger than we presumed, and what we thought was unbearable was nothing of the sort. Music draws forth these subterranean feelings and simultaneously rescues us from them.”

This is the power of performance. Its impact may not be to immediately change laws or depose leaders. But it can create emotional cohesion and resonance among a wide and diverse range of people. It can stir our hearts and minds and leave us deeply and fundamentally changed. Performance can alter the way we relate to one another and the actions each of us as audience members takes the next day and the day after that.

Let’s hold people accountable. This is important and necessary. But let’s not allow our cynicism or the delicate nuances of our language to lead us to sacrifice the transformative function of performance to reshape our individual hearts or our collective conscience.

Listen for the drummers and the orators in our midst and walk alongside them. They will change you.

Wishing you music that propels you forward and words that lift your heart,

Alicia

A few things I found helpful & hopeful this week…

Millions Stood Up by Rebecca Solnit

If you think someone else in your life might need some hope, please share. It’s always easier to hold onto hope when we’re not doing it alone.

And if you appreciated this post and are not already a subscriber, please consider subscribing to Notes on Hope.